Ankylosaurs, like probably most other dinosaurs, were

landlubbing, terrestrial animals without obvious aquatic adaptations. And yet,

surprisingly, their fossils are found in marine sedimentary environments more

often than most other dinosaurs (except hadrosaurs). Some, like

Aletopelta,

wound up in shallow or lagoonal environments -

Aletopelta's carcass became a

reef! - but some, like the

Suncor nodosaurid, wound up far away from shore.

Aletopelta! See if you can spot the oyster marks, invertebrates, and shark teeth around the pelvis and legs.

I wanted to look into this phenomenon in a bit

more detail than it had been investigated previously, and with my work on

ankylosaurid phylogenetics and biogeography published last year the time was right

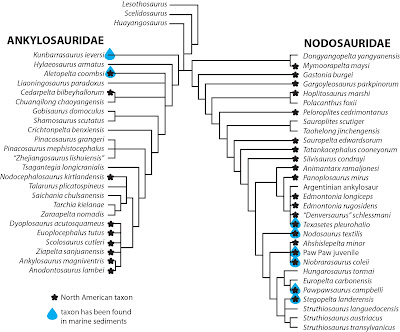

to dive into marine ankylosaurs. I added in more taxa into my ankylosaurid

character matrix to check whether there were any secret ankylosaurids hiding in

the taxa I didn't previously include.

Surprisingly, Hylaeosaurus popped out as

a basal ankylosaurid in this analysis, an intriguing result that I think needs

further investigation but could be really interesting. Mostly everything else that should be a nodosaurid was a nodosaurid, and I got surprisingly good resolution in the Nodosauridae, but take the interrelationships there with a tiny grain of salt given that I didn't make any new characters for this analysis and the existing character set is geared towards ankylosaurids.

Next up, I downloaded a dataset of all the ankylosaur

occurrences in the Paleobiology Database and went through each entry (more than

500!) to verify whether or not the specimens were ankylosaurids, nodosaurids,

or if we couldn't tell for sure, and their depositional environment. With that data in hand, we wanted to know what the

geographic distribution of ankylosaur marine occurrences looked like, and here

it is:

Lots of ankylosaurs in the northern hemisphere, not so many

in the southern hemisphere. More than half of marine ankylosaurs occur in North

America, which is perhaps unsurprising given that North America had a bad habit

of being underwater for a lot of the Cretaceous. When we exclude indeterminate

occurrences, we get an ankylosaurid-nodosaurid marine-terrestrial split that

looks like this:

In North America and Asia, the distribution of ankylosaurs in different environments is statistically significant, but it isn't in Europe (and remember, Hylaeosaurus hasn't previously been found as an ankylosaurid so there might not even be ankylosaurids in Europe).

Although there are nodosaurids and ankylosaurids in Asia, I don't think they overlapped very much in time - nodosaurids disappear from the Asian fossil record around the time that ankylosaurids appear. North America is unique in that it is the only place where we find both clades of ankylosaurs overlapping for significant chunks of time, so I wanted to know whether or not the significant marine-terrestrial dichotomy holds up in different time intervals within North America. We decided to divide up the dataset by the ebb and flow of the Western Interior Seaway, or, transgressive-regressive cycles. There were several major cycles well known to sequence stratigraphers and other geologists, and it seemed like a logical way to look at how the seaway influenced marine occurrences in ankylosaurs. How does that data look?

Like this! Unsurprisingly, a huge number of ankylosaur occurrences are clustered at the end of the Cretaceous, largely because of the Dinosaur Park Formation and its well-documented dinosaur fauna. But focus on the marine occurrences and an interesting pattern emerges - while the number of terrestrial occurrences fluctuates widely, the number of marine occurrences stays relatively steady. We think this reflects the absence of terrestrial outcrops for a chunk of the mid Cretaceous when sea levels were at their very highest - in other words, although there's a greater proportion of marine occurrences in the middle, they don't really increase in absolute terms and the proportion is being driven by the drop in terrestrial occurrences.

And here's what it looks like when we exclude indeterminate ankylosaurs. Unfortunately, this is the point at which we lose statistical power for most of the data, which means we can't really interpret most of the results with any confidence. Plus, there is a good chunk of time in the mid Cretaceous in which there are no ankylosaurids known at all, which probably represents a regional extinction for this group of dinosaurs. BUT, one time bin shows a significant difference between depositional environment and clade - the Kiowa-Skull Creek cycle in the Albian-Cenomanian.

What does it all mean? For one thing, breaking down the global ankylosaur dataset still yields enough statistical power for some analyses to be useful and give us more insight into biogeographic patterns...up to a point. Secondly, there really does seem to be something about nodosaurids that makes them wind up in marine environments more often than ankylosaurids. And this begs the question: why don't ankylosaurids like the beach? Given that ankylosaurids disappear from North America right around the time that sea levels rose to their highest point, could rising sea levels have led to the extinction of North American ankylosaurids? Did sea levels need to drop substantially before the inland, somewhat desert-dwelling Asian ankylosaurids migrated back into North America in the latest Cretaceous? Did ankylosaurids avoid the European archipelago because they didn't like to get their feet wet? I don't have definite answers yet, but I find this pattern terribly interesting and I'm sure this isn't the last we'll be looking at this weird split in environmental preferences between ankylosaurids and nodosaurids.